By: Dean Wang | December 2014

Ever since China embraced the Open Door Policy in 1978, the country opened its borders to the world economy and has not looked back since. Within decades, China’s economy made leaps and bounds like no other country in history. By 2010, China had overtaken Japan as the second largest economy in the world, and many economists expect China to overtake the United States by as early as 2020. However, with exponential growth comes exponential consumption, as the world’s most populous nation is also the world’s largest energy consumer and consequently is the leading emitter of CO2. Although the Chinese Government has become self-aware of the environmental issues the country faces, in the last two decades the government has taken drastic steps to alleviate the growing environmental concerns both domestically and internationally. From a distance, some of the drastic environmental goals China has proposed seem improbable; many skeptics believe China simply cannot “Go Green”, as the hungry nation will only continue to consume more to sustain its economic growth. Is China’s green campaign a false goal or an achievable reality? What are China’s potential alternative sources of energy consumption? Can China balance its economic growth with its environmental sustainability goals before the world reaches the “point of no return”? China’s road to sustainability is not only a recent phenomenon but an achievable one. While China’s environmental goals will not only hope to drastically change the environmental hazards the nation has brought upon itself, but China’s future policies will also without a doubt have an immediate effect on the hazardous trans-boundary pollution that has affected the bordering nations surrounding China and the entire global climate.

It may be difficult to pinpoint which domestic or international environmental issue caused the tipping point for China’s declaration and commitment to sustainable development but the moment it was officially pushed to the top country agenda was in 2013, when President Xi Jinping outlined sustainability and environmental preservation as a top priority in his Congress party speech “China’s Dream”. China is currently the largest energy consumer in the world, with the United State as a close second. China is also ranked first in coal consumption and second in oil consumption for energy which comes as no surprise that China is also the single largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

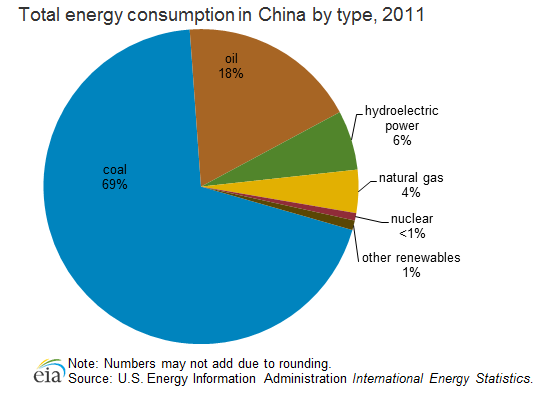

Almost 70% of China’s total energy consumption comes from the energy generated by the burning of coal, while 18% comes from oil, 6% from hydro-electric sources, 4% from natural gas and nuclear energy (Eia.gov:China). Coal is China’s main energy source and undoubtedly the dirtiest. The effects of coal burning on Chinese cities have caught the attention of both domestic and international scrutiny as many of China’s immediate visible environmental hazards have come from coal. While Coal is considered the dirtiest source of energy, China has embraced the prospect of using “clean coal” in the future. China is proposing to use “clean coal”, which has fewer levels of ash and sulfur in its composite. This proposal alone has caused panic in global coal trade, as for instance, Australia, one of the largest exporters of coal in the world, has been forced to scramble to look at alternative buyers for its humongous coal deposit (Ahmad).

China’s pledge to reduce the hazardous effects of coal can not only be seen in how its energy policies are shifting, but also through the drastic reductions of coal burning. For example, earlier this year China unveiled a new energy plan, The Energy Development Strategy Action Plan (2014-2020), which most importantly sets up a cap on national coal consumption for 2020. The Action Plan has pledged an annual primary energy consumption set at 4.8 billion tonnes of standard coal until 2020 (Bo). China’s use of coal cannot be undercut without thinking about its ramifications on economic growth as the nation sits on one of the largest coal reserves in the world. The Chinese Government has long been divided on the issue of the speed at which coal should be substituted for its energy purposes. The notion that coal is harmful to the environment is only a recent realization by policy makers as previously coal was only lauded as cheap and abundant to the Chinese cause. Internally, transitioning from coal to alternative sources of energy presents other problems that state officials often echo, and that is the potential loss of jobs. The Chinese coal industry is not only a provider of jobs to several hundred thousand workers. But in many local cities it is often the economic engine that communities survive on.

China’s pledge to advance environmental sustainability has not just come from verbal pledges but from published economic goals the government releases to the public. One major pledge is through the national government’s Five Year Plan (FYP). The latest FYP which was also the 12th ever established, aimed to “reduce fossil fuel consumption, promote low-carbon energy sources and reconstruct China’s economy”. Some of the goals the FYP has set for China have been ambitious to say the very least. The current plan aims for a 16% reduction in total energy consumption per unit of GDP and a 17% reduction in carbon intensity. While not meeting these goals at the end of each of the five years may not subject the country to punishment or policy consequences, the FYPs have self-servingly done well in coming close to reaching each goal the country has set. For example, in the 11th FYP, China came close to meeting the reduction goal of its energy intensity by 20% as it has just missed the mark by reaching 19.1 % (Lewis). This commitment to non-binding promises pageants the Chinese Government’s determination to meeting the proposed energy goals it has established for itself.

China’s Pollution Both Domestically and Internationally

In the mid-2000s, China’s pollution had finally reached alarming rates. China’s visible pollution hazards were later magnified on the international stage as China was host to the 2008 Olympics. The environmental pollution was so scrutinized, it became a big talking point that year and often it overshadowed the summer games. While smog and ash covering buildings was the first visible problems with China’s big cities, later it was confirmed that only about 1 % of China’s cities’ air were considered safe to live in by European Union standards. Almost half a billion people also lacked the necessary resources to get access to safe and clean drinking water. As China’s dirty coal plants produce dangerous amounts of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, China’s cities are engulfed in a perpetual haze, and its residents have suffered the detrimental health effects, evidenced by the rise of cancer and respiratory diseases as the top causes of death in the country (Kahn).

China also has a huge impact on its immediate neighbors as well having its fingerprints on the global climate. Regionally, China’s pollution can be traced most proximately by its neighboring countries. Despite the fact that China has done much to alleviate its quality of air by taking measures such as “closing outdated factories, relocating heavily polluting facilities, promoting the use of renewable energy, and regulating the number of cars on the road in mega-cities”, air pollution is still at hazardous levels, as neighboring Japan and South Korea can still feel the brunt of the pollution. Due to their proximity and geological location, which subjects them to a downwind direction of mainland China, Japan and South Korea have monitored the entering of PM 2.5 in their respective airspaces. PM 2.5 is referred to the particulate matter of an airborne pollutant which is less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (Tanabe). PM 2.5 is considered a health hazard because of the small size of the particulate matter as it can be passed through human lungs, which can later cause respiratory health issues.

The recent influx of China’s PM 2.5 into its neighboring countries is not the first time China has been the culprit of being the emitter of a trans-boundary pollutant. In the 1990’s there was a huge problem with sulfur oxide and in the early 2000s, as it became the seasonal yellow dust that plagued South Korea and Japan. The trans-boundary pollution issue is both a problematic and complicated issue because of the political tensions between South Korea, Japan and China caused by historical grievances mostly unrelated to the environment. While there is dialogue between the nations, often environmental issues are shoved to the bottom of the totem pole in favor of seemingly more immediate issues of national security and regional economics. More importantly there is no clear rule of law setup or a commission with actual power in place to combat or police the pollution between the three neighboring countries. In the 1970s, trans-boundary pollution was a big cause of the acidification of many of the ecosystems in Europe, and the European Union solved their issue by help setting up the Convention on Long-Range Trans-Boundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) which solved a lot of the problems in member states of the EU. However, such a commission is non-existent between China and its immediate neighbors (Asuka, 5).

Perhaps a growing source of a major polluter is the number of vehicles China amasses. The United States is actually the leading manufacturer and auto consumer in the world with roughly a quarter billion cars registered as of 2007 and China only at about 62 million as of 2010. China’s number may seem small but it is a growing issue as the alarming rate at which China is pumping out cars onto its street is at exponential rates, as there were only about 5 million cars on the roads in China (ChinaAutoWeb). China with foresight has done well to combat this contributor to the environmental harm as it was the first developing nation to implement a fuel-efficiency standard for vehicles in 2004. China’s vehicular emission standards today are far more strict and regulated than U.S standards and are the third most stringent behind only the European Union and Japan (Remais, 894).

Many experts argue that China’s energy consumption simply just cannot be slowed down because neither the insatiable appetite of the Chinese economy can be contained nor does the Chinese government have the willingness to slow down. While China’s energy consumption per capita is lower than any other developed nation, potential concern for the future arises when considering a shift in energy consumption from the industry to the individual, which would cause energy consumption to increase even further. Despite what the argument may be for whether China’s growth will slow down, it is more important to take into consideration how China goes about consuming its energy rather than how much energy China will consume. China’s sole path to a more sustainable energy policy will not only immediately affect the global climate but with the Chinese already investing heavily in alternative sources of energy, it will only force a shift in the global energy policy.

Alternative Sources of Energy

Though China has ambitiously set goals to cut its dependency on coal, the country also has gone in the other direction and invested heavily in alternative sources of energy. China certainly has a lot of critics and it is hard to defend one of the world’s biggest polluters but we must take into account China’s green efforts, as the country has already started on its massive campaign to reach sustainability. For example, China invested $58.4 billion in alternatives energy sources like wind and solar in 2012. China today is actually the leading investor in the world of alternative energy. The previously mentioned shift to clean coal is just one of many efforts to fill up the remaining pie chart of China’s energy usage. The government has proactively initiated its investments in alternative sources of energy to fill the void when the day coal will be dramatically phased out. One such investment by China is the recent $2.5 billion made by state owned China Petroleum and Chemical Corp in Shale gas. China is attempting to increase shale gas output by 40% by the end of 2014. While Shale gas represents less than 4% of the nation’s total energy source, China is in a unique predicament as it tries to replicate the shale boom previously experienced in the United States in the late 1990s. China’s potential boom however, is a much bigger one as it currently sits on twice as much shale deposits than the U.S. To put into perspective just how much shale gas China is projected to increase, at the end of this year, China is aiming to produce 1.5 billion cubic meters of shale. Next year, the government aims to produce almost six times that amount and by 2017, that number is aimed at reaching an estimated 15 billion cubic meters (Bloomberg).

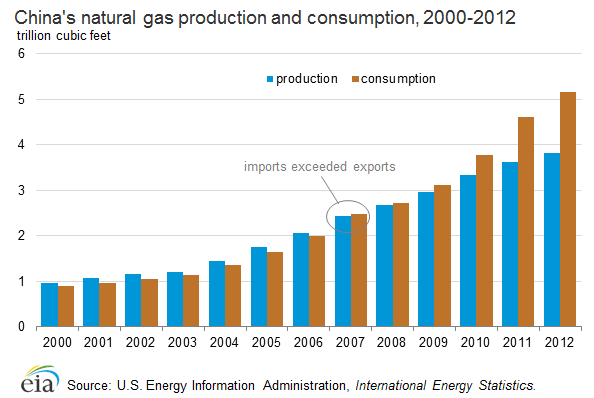

If China’s commitment to undercutting its reliance on coal is still not convincing, then it cannot be made any clearer than China’s decision to sign a $400 billion natural gas contract with Russia earlier this year. The contract entails Russia supplying 38 billion meters of Russian gas supply through it’s yet to be built pipelines. Although the contract was struck under many political undertones in the midst of Russia facing the Ukraine crisis, China nonetheless took the opportunity to secure its own supply of both pipeline gas and liquefied natural gas (Nakano).

It was only ten years ago that almost all of the world’s photovoltaic panels were coming out of the United States, Japan and Germany. However by the mid-2000s, China has already caught up with the top solar panel manufacturers and leaped into third place, becoming the third largest manufacturer. Today, China embodies 4 out of the 5 top largest solar panel manufacturers in the world and it is only taking on an even bigger role in the photovoltaic industry. Today, Chinese solar companies in total manufacture about 50 million panels a year, which is more than half the world’s annual supply. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the country’s sudden output is that the industry is thriving and not just because of the usual “cheap labor” title that comes with Chinese manufacturing but through efficient technology. The manufacturing of Chinese solar panels requires the same expensive raw materials such as silicon which a foreign manufacturer would require. China has exceeded its predecessors in constructing faster and cheaper factories, complemented with a “streamlined permitting process” which speeds up the licensing and logistics aspects of manufacturing (Bullis). These is interesting as most of these top solar companies are either state-owned or state sponsored which gives them an advantage as the companies often see little legal hurdles, thus speeding up both construction and output, unmatched by any other country in the world. Solar energy is arguably mankind’s most abundant energy source but the technology and the expensive cost of construction of contemporary solar panels has kept the energy source at bay. While it may take decades, maybe even centuries until we can fully harness the power of the sun, China has attempted to take a lead in both global investments and manufacturing in hopes to bring solar energy to the forefront of renewable energy consumption.

In a similar juncture, the wind energy sector of China shares some of the same advantages solar energy has reveled in. Like the solar energy sector, most of the top wind turbine manufacturing companies are state-owned and therefore enjoyed rapid growth in the construction of wind factories. Not only was China the largest wind turbine consumer in 2010, but its four largest turbine manufacturers were also evidently in the top 10 biggest worldwide. Despite its quick rise in becoming a manufacturing giant, China’s wind energy sector is still in the maturing stages of development. Unlike solar, the wind turbine manufacturing sector is oriented towards the domestic market. Domestic competition was high at the startup of the industry but over time demand has become oversupplied forcing the Chinese investors to look to international markets. One value of investing the Chinese are trying to capitalize on is the learning and acquirement of new technology in the wind sector. For example, Chinese turbine maker XEMC bought out Darwind, the leading Dutch offshore wind turbine producer in 2009 for $13.6 million. Similarly other Chinese wind manufacturers have followed suit and acquired stakes in a number of established foreign companies in the likes of industry leaders like Japan and Germany (Tan, 11-12).

Offshore wind technology is something the Chinese have come to take particular interest in. Chinese investors have obviously seen offshore wind farms as a significant potential future energy source. China is the leader in wind energy in terms of installed wind power capacity, currently at about a nationwide capacity of 62.36GW (Li, 2). However, growth for wind farms on land seems limited as a majority of Chinese wind development comes from one region of the country, known as “The Three Northern Area”; this region is comprised of 14 provinces and cities including Inner Mongolia (Li, 8). For this reason China has found significant interest in developing and adding offshore wind energy production into its energy consumption. By the end of 2011, an estimated 242.5MW installed capacity of offshore wind power had been completed and not to mention the 2.3GW offshore wind projects that are still in the early stages development. Imaginably, the most ambitious energy plans of all is the aforementioned 12th FYPs goal of constructing 5GW offshore wind power stations by 2015 and 30 GW offshore plants by 2020 (Li, 15-16).

China’s history with nuclear technology is an interesting one as the Communist Party had a nuclear weapons program before it had an energy program. China’s nuclear energy industry was hindered much by tensions of the Cold War as national security was a top priority at the time and energy consumption, of course, was nowhere near the appetite China has acquired today. However like the rest of China, after the Open Door Policy, China’s leaders drastically shifted the economy to a more market-driven economy and unintentionally kick started its nuclear energy program. Within two decades, China would formalize the nuclear transition from a military to a civilian one with the creation of the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) in 1989. By 2006, China’s commitment to nuclear power was stamped with its formation of its ‘‘Medium and Long-term Nuclear Power Development Plan’’, which evidently outlines its goal to increase the country’s nuclear capacity to about 40 Gwe by the year 2020 (Hinze, 772).

Since the 2011 Fukushima Daichi nuclear power plant disaster, the global stage for nuclear energy construction came to a standstill. Public scrutiny of nuclear energy was first made present with the disasters of Chernobyl and the Three-Mile Island Accident, and after Fukushima, it was at an all-time high. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had declared Japan would be nuclear-free by 2050 in the midst of the hysteria as the internet age came to see firsthand the unmatched hazard that may come with this high risk-high reward source of energy. China too halted all nuclear construction in 2012, but resumed soon after. China quickly has gotten back on track with its ambitious plans to give nuclear energy a larger role in China’s energy consumption. Many experts including ones from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) continue to position that nuclear energy is the main defense against all aspects of climate change. To the immediate attention, Nuclear energy emits virtually no air pollution, no greenhouse gases, and has a relatively low operational cost. China however has taken a step further and has its eyes set on a cleaner and even higher output of nuclear energy with plans to develop new advanced thorium reactors, the first of its kind in just under ten years (Akerlind).

While contemporary nuclear reactors use Uranium as the main source for fuel, Thorium is viewed to be cleaner, safer and much more abundant raw material. China has proposed to develop a thorium-fueled molten-salt nuclear reactor in the next decade or so, China really picked up where a lot of other countries left off. The United States in the 1960s and 1970s conducted intensive thorium based research on potentially powering the element as a fuel; however, the programs were eventually scrapped after lack of funding and having little success. Chinas moves to step away from Uranium not just from an environmental standpoint but from a safety concern one. As public opinion in modern day China has become very influential and powerful, the narrative Chinese officials seek to receive is one of safety first and at the same time mindfulness in the shift of energy sources to potential thorium powered molten- salt reactors. Molten-salt reactors are not only argued to be cleaner but the reactors can consume various nuclear fuel types including various stocks of nuclear waste fuels. This alone can be one of a few ways modern technology can answer the question of how to get rid of nuclear waste (Martin).

As mentioned before, hydroelectricity is the only source of renewable energy that has any significant contribution to China’s energy consumption, with roughly 6% of the total energy pie chart. China’s hydroelectricity ambitions perhaps caught the attention of the world when China built the world’s largest dam in the Three Gorges Dam in Hubei Province. The mega dam stirred controversy from both domestic and international critics as the dam was said to be fatal to local ecosystems, as the manmade displacement of water was both harmful to marine life and related environments. Also, an unprecedented amount of people who previously lived along the waterways were forcefully displaced. Despite the criticism, the dam was built and today, boasts a potential 84 billion kilowatt hours of electricity created from the project. While the Three Gorges Dam is by far the biggest project, China has aggressively planned and constructed thousands of other small to medium size dams around the country. One big obstacle China’s hydroelectricity ambitions have is the geographical challenges the country faces; most of China’s major cities are on the east coast while most of the plants that have been built have been routed along the western regions of the country. The potential electricity transfer and transmission from west to east could mean further detrimental harm to the local environment and infrastructures (Zhou, 3759). This perhaps brings us to China’s biggest navigator of its “Green Campaign”, and that is public opinion.

Public Opinion

Public opinion has by far become the single most influential factor in all aspect of Chinese Government. Although China is still theoretically speaking, ruled by the Communist government, its quasi market driven economy has really pushed it to the forefront of global economics and China shows no signs of fixing what is not broken. For the past two decades, the Chinese population has enjoyed record increasing standards of living and wealth and consequently, has also gained increased strength in the public voice. This can be seen distinctly in the environmental voices China has come to hear since the 2000s, with the public building awareness of the many hazards the government has caused.

Chinese environmental protesters over the past few years have consistently won protests and have had significant influence on local officials and policy makers. While it can be pointed out that the civilian population is not only more educated today, there is also significant physical evidence protesters can point to, like the infamous “smog” covering the streets of major cities in China. For example in 2012, the city of Shifang’s officials announced the construction of a $1.6 billion smelter plant in the district. In response, thousands of angry protesters showed up and enacted sit-ins at government buildings and this often resulted in violent clashes with the local police. The result was the cancellation of the project altogether. Similar episodes were heard all over the country, including Hong Kong, where a coal fired power plant was scrapped for construction after more than 30,000 people marched in protest. Not only are the Chinese citizenry more brave today than say 20 years ago, the country also boasts the most internet users of any country in the world. Thus, it’s no wonder they are more aware and organized than any group before them (Bradsher).

China and U.S Cooperation

Perhaps the single most important ingredient in both the world and China’s path to sustainability depends on the cooperation and relationship of China and the United States. On paper it makes sense, as the world’s two largest economies are also evidently two of its largest polluters. However it is not all bad, as there is a positive in these standings; this puts China and the United States in a unique position to not only influence environmental policy change, but to make a major immediate physical impact on the global climate, just by gearing its environment policies towards a more sustainable and environmentally friendly one.

The silver lining here is that while the two economic giants may seem destructive to our global climate, they are consequently also the leading investors in the development of clean energy. In 2012, the United States invested $30.4 billion dollars in both wind and solar, while China led the way by investing $58.4 billion. The two countries’ past record of cooperation has already had significant impacts on climate change as just last year, China and the United States reached a landmark agreement on a framework to reduce Hydro Fluorocarbons (HFCs). The phase down of HFCs is seen by most experts as one of the more immediate ways to dampen the harm on the Ozone layer. Since the White House has taken charge in the phase down of HFCs, it has also gotten the voluntary commitment of some of the United States’ biggest companies including Coca-Cola, Pepsi and DuPont. DuPont is of special significance as it was the company that invented the fluorinated refrigerant, which is the main component used in modern day appliances that has contributed heavily to the influx of HFC. The agreement so far has estimates that put the reduction at about “…700 million metric tons of carbon dioxide through 2025. That is about 1.5 percent of the world’s 2010 greenhouse gas emissions, or the same as taking 15 million cars off the road for 10 years” (Davenport).

The cooperation of the two biggest polluters is crucial to the global movement in alleviating climate change. Not only do these two giants have the capital and the incentive to do so, by doing so, the two biggest economies can set a leading example by paving the way for commercial sustainability. U.S – China collaborations such as the US-China Clean Energy Research Center (CERC), has already established a relationship that fosters such development. CERC not only moves to develop new technology for sustainability but with the collaboration the two consumer giants, has set out to protect intellectual property concerning sustainable development (Forbes).

The Environmental Protection Agency has a distinctive partnership with China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). While the two agencies have done collaborative work for over three decades, the agencies have worked together on a variety of other issues ranging from pollution, emergency preparedness to environmental law (EPA). The United States and China also have established a Ten Year Framework for Energy and Environment Cooperation (TYF). A similar mission statements to CERC, the TYFs facilitates the exchange of information and ideas in the hopes it can nurture new and better solutions to solve the both the energy and environmental crisis.

Not everything is sunshine and rainbows when it comes to fostering clean energy and promoting environmental cooperation between China and the United States. It must be a reminder that the two economic giants are also fighting for the position of the global hegemon. Most of the barriers the two countries faces are economic ones. An event that comes to mind is previous flood of subsidized Chinese manufactured solar panels that was shunned by the U.S market because it was thought to be harmful to U.S solar panel manufacturers. This is relevant as a major investment barrier for Chinese manufacturers, as many investors see the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) as a problematic hurdle because it often is the final stand in approving cross-national energy deals (Zhao).

When it came to cutting down CO2 emissions, the United States’ rhetoric in the past years have always been to point to China and cite that if China refuses to cut down then why should they. As one of the leading investors and promoters of green energy, the United States must cooperate and assist China with its energy transition, as it would harbor many benefits to itself. This is not just for the commercial and economic opportunities, as China’s potential future reliance on Middle East oil and reduction in greenhouse gases can be matters of national interest to the United States (Kim, 33).

Intrinsically China and the United States’ actions will be reliant on their own national interests. The United States is in a scurry to hold on to its economic hegemony while China on the other hand has ambitious economic plans that needs to be balanced out with the severe pollution problem the country has caused. China’s road to sustainability is certainly a feasible one but it is certainly not an easy one. The greater challenge is perhaps how fast the country can “Go Green” as there is no set date to meet but there is a deadline, environmentally speaking. Many experts have different measurements for the point of no return in climate change but the most popular one is the 2°C target. It is theorized that the global rise in temperature should be limited to 2°C, as anything past that the Earth’s ecosystem will tumble into a series of irreversible chaotic scenarios that will put the Earth on a rapid course to climate devastation. Now it may seem frivolous to suggest that the global climate rests on just China and the United States but the reality is that it does start with their commitments and actions. Some can take comfort that China has expanded its investments in a plethora of alternative sources of energy in hopes to reduce pollution and become more sustainable in terms of energy. Even though many of the internal environmental and energy policy have not been binding, the Chinese have done well to either meet their goals or come close to meeting them.

China and the United States are in a unique position to influence environmental policy change and make a major immediate impact not just on the global economy but on the overall global climate. China it seems will undoubtedly pass the United States as the world’s largest economy and on top of that its energy consumption will only rise. The important thing however, is to keep in mind that it is about how the countries continue to consume not how much they will consume. China’s path to green has been aggressively pursued and supported by both its people and government. The only question left is, will China make its adjustments in time before the “point of no return” and what kind of supportive role will the United States play in this time of transition? Only time will tell.

Works Cited

Ahmad, Shabbir. “China’s War on Pollution Could Leave Australian Coal out in the Cold.” Chinadialogue. N.p., 25 Sept. 2014. Web. <https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/7346-China-s-war-on-pollution-could-leave-Australian-coal-out-in-the-cold>.

Akerlind, Ingrid. “Nuclear Energy Renaissance Set to Move Ahead Without U.S.”ENERGY INNOVATION (2014): n. pag. Thirdway.org. The Clean Energy Program, Apr. 2014. Web. <http://content.thirdway.org/publications/851/Third_Way_Report_-_Nuclear_Energy_Renaissance_Set_to_Move_Ahead_Without_U.S..pdf>.

Asuka, Jusen. “Sino-Japan Collaboration for Air-pollution.” Sino-Japan Collaboration for Air-pollution. Institute for Global Environmental Studies, Apr. 2013. Web. Dec. 2014. <http://www.isn.ethz.ch/Digital-Library/Publications/Detail/?ots591=0c54e3b3-1e9c-be1e-2c24-a6a8c7060233&lng=en&id=168865>.

Bo, Xiang. “China Unveils Energy Strategy, Targets for 2020 – Xinhua | English.news.cn.” China Unveils Energy Strategy, Targets for 2020 – Xinhua | English.news.cn. Xinhuanet, 19 Nov. 2014. Web.

Bradsher, Keith. “Bolder Protests Against Pollution Win Project’s Defeat in China.”The New York Times. The New York Times, 04 July 2012. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/05/world/asia/chinese-officials-cancel-plant-project-amid-protests.html>.

Bullis, Kevin. “The Chinese Solar Machine.” TechnoloyReview.com. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 19 Dec. 2011. Web. <http://www.technologyreview.com/featuredstory/426393/the-chinese-solar-machine/>.

ChinaAutoWeb .”How Many Cars Are There in China?” ChinaAutoWeb.com. N.p., 5 Sept. 2010. Web. Dec. 2014. <http://chinaautoweb.com/2010/09/how-many-cars-are-there-in-china/>.

Davenport, Coral. “U.S. Moves to Reduce Global Warming Emissions.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 16 Sept. 2014. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/17/us/hfc-emissions-cut-under-agreement.html>.

Eia.gov :China. Rep. U.S Energy Information Administration, 2 Feb. 2014. Web. <http://www.eia.gov/countries/analysisbriefs/China/china.pdf>.

EPA. Collaboration with China. Environmental Protection Agency, n.d. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. http://www2.epa.gov/international-cooperation/epa-collaboration-china#agreements

Hinze, Jonathan, Yun Zhou, Christhian Rengifo and Peipei Chen. “Is China Ready for Its Nuclear Expansion?” Energy Policy 39.2 (2011): 771-81. Science Direct. Web.

Kahn, Joseph, and Jim Yardley. “As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes.”The New York Times. The New York Times, 25 Aug. 2007. Web. <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/26/world/asia/26china.html?oref=login>.

Kim, Margret J. “ENVIRONMENTAL LAW: CHINA’S ENERGY SECURITY AND THE CLIMATE CHANGE CONUNDRUM.” GPSolo 22.6, The Best Articles Published by the ABA (2005): 32-33. JSTOR. Web. 11 Oct. 2014.

Lewis, Joanna. “Energy and Climate Goals of China’s 12th Five-Year Plan.” C2es.org. Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, Mar. 2011. Web. <http://www.c2es.org/international/key-country-policies/china/energy-climate-goals-twelfth-five-year-plan>.

Li, JungFeng. “China Wind Energy Outlook 2012.” Global Wind Energy Council (2012): n. pag. Web. 17 Nov. 2014. <http://www.gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/China-Outlook-2012-EN.pdf>.Nakano, Jane, and Edward C. Chow. “Russia-China Natural Gas Agreement Crosses the Finish Line.” CSIS.org. Center for Strategic and International Studies, 28 May 2014. Web. <http://csis.org/publication/russia-china-natural-gas-agreement-crosses-finish-line>.

Martin, Richard. “China Takes Lead in Race for Clean Nuclear Power.” Wired.com. Conde Nast Digital, 30 Jan. 2011. Web. 1 Nov. 2014. <http://www.wired.com/2011/02/china-thorium-power/>.

Remais, Justin V., and Junfeng Zhang. “Environmental Lessons from China: Finding Promising Policies in Unlikely Places.” Environmental Health Perspectives 119.7 (2011): 893-95. JSTOR. Web.

“Sinopec, PetroChina Plan 40% Growth in Shale Output to Meet Goal.”Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 15 Nov. 2009. Web. <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-09-17/sinopec-petrochina-plan-40-growth-in-shale-output-to-meet-goal.html>.

Tanabe, Nobuhiro. “Transboundary Air Pollution from China | Ecology Global Network.” Ecology.com. Ecology Global Network, 22 Nov. 2013. Web. 11 Oct. 2014.

Tan, Xiaomei, Yingzhen Zhao, Clifford Polycarp, and Jianwen Bai. CHINA’S OVERSEAS INVESTMENTS IN THE WIND AND SOLAR INDUSTRIES: TRENDS AND DRIVERSWorking Paper (2013): n. pag. Wri.org. World Resources Institute, Apr. 2013. Web. <http://www.wri.org/sites/default/files/pdf/chinas_overseas_investments_in_wind_and_solar_trends_and_drivers.pdf>

U.S State Dept. “U.S.-China Ten Year Framework for Energy and Environment Cooperation”. U.S. Department of State, 11 Apr. 2012. Web. 2014. <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/04/187736.htm>.

Zhao, Yingzhen. “Why Is China Investing So Much in U.S. Solar and Wind?” Why Is China Investing So Much in U.S. Solar and Wind? World Resources Institute, June 2012. Web. <http://www.wri.org/blog/2013/06/why-china-investing-so-much-us-solar-and-wind>.

Zhou, Yun. “Why Is China Going Nuclear?” Energy Policy 38.7 (2010): 3755-762. Science Direct. Web.